Can you think of a moment in your life when you knew that nothing would ever be the same?

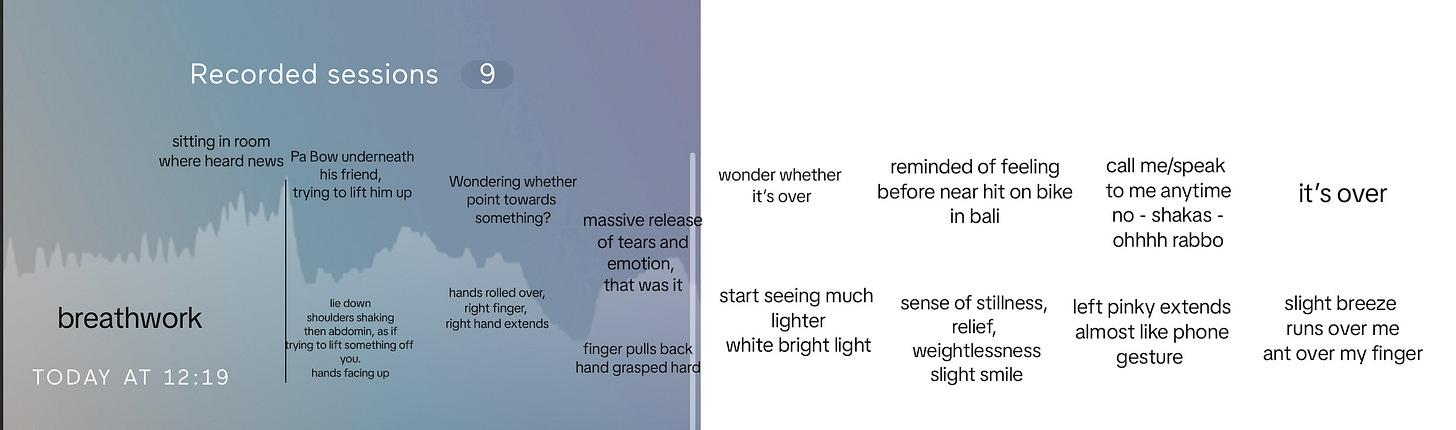

I was on my back, eyes closed and shoulders shaking. Slowly, the trembling travelled down to my abdomen. My hips rose off the floor, and my hands pulled away from me, palms up as if attached to marionette strings from my wrists.

Instead of sitting on the edge of my bed, where I was moments ago, I was now attempting to lift, as you would if you were moving a heavy log, using your hips as a pivot point, heaving and twisting with full grit. But instead of a log, it was an unconscious body. That of my grandfather's best friend who was trapped in the weeds underwater.

I trembled as tears came to my eyes, not streaming, but an unmistakable acknowledgment that the doors of our emotional cabinet had swung open, the doors we usually keep shut under lock and key.

Without warning, my hand rolled over with the right index finger extending.

Was I supposed to look at something? Was I blaming something or someone?

It didn’t matter. I’d learnt by now not to question it. As soon as you question, try to solve, try to outthink a feeling, you pull yourself away from what is being revealed to you. What needs to be known, will be known, all in good time.

My breathing slowed, my heart rate dropped, and I thought maybe it was all over. But I was wrong. My index finger, which had extended and lay somewhat limp, pulled back with such force that an undeniable truth rushed inside me before I could even ponder its relevance.

I was pulling back the brake on my friend’s motorbike.

My veins were popping with the intensity of the grip, and on this occasion, it wasn’t a knocking at the emotional door, the well had sprung, and tears overwhelmed me.

After some time sobbing, clinching, and wrestling in my body as my soul shot around me like a pinball within a straitjacket, I began to relax.

My focus was raised to my eyes whilst still closed. A white light became more prominent in the projector that plays inside our lids, the brightness increasing out of the scattering of tiny beams. It softened to a glow, and a feeling of serenity came over me.

Again, without hesitation, I knew what that feeling was. The last time I had that feeling was about a year ago, as I was riding my own motorbike to what seemed like a certain death.

I had the throttle pulled back as hard as I could, but a dreaded reality dawned on me. In the face of the full force of my efforts, it was not enough. I wasn’t going to make it. I was attempting to overtake a long transport truck on a single-lane highway. But as I was doing so, another truck came over the crest and began cascading down the mountain towards me. That incline was the miscalculation. His weight was increasing his acceleration. My weight and fight against this side of the mountain was decreasing my acceleration. A narrowing of opposites.

Time paused its mortal dance. For this incredibly elongated space, that made no sense to the hands on a clock face, I felt still. I felt full acceptance. I felt bliss. The dread that cloaked me vanished entirely, the somersaults in my stomach ceased, and my wide-opened eyes relaxed.

Inexplicably, as you can no doubt work out, I made it through the gap. To this day I can not explain how. All logic had the walls these two trucks formed, as closed by the time I could possibly find a clear exit. And yet I did.

A smile came to my face whilst I lay on my back and a re-commenced movement in my little finger took my focus away from that soft white glow. It released its grip on the invisible brake lever and, along with my thumb, fell into a posture that could say ‘call me’ in sign language. What we might do through a glass window to a friend on the other side unable to hear our words.

I wondered, is that a reminder I can enter this line of communication whenever I want? Stop thinking Jason, you know that’s not how this works.

Then I saw Marc in my mind’s eye. My mate I wished to pull the motorbike brake for, who wasn’t as lucky. He would see me from a hundred metres away at the beach and scream out “Oh Rabbo!” (my childhood nickname) whilst doing a ‘shakas’ as you might have seen surfers do in a display of enthusiasm and community.

A light breeze I hadn’t noticed the whole session blew and an ant crawled over my hand that I couldn’t ignore. So I opened my eyes. I brushed the ant away and smiled wider. It’s over. It’s not forgotten, it never will be, and that’s not the goal. But I can move on, without guilt, in his name, with his permission.

I directly annotated what I had been through on a screenshot of an app I was using to track my heart rate. Unfortunately, the timer stopped, but I continued with the best guess at accurately timed spacing.

C-PTSD Sequencing

That all may sound disjointed. That all might sound anti-chronological, multi-contextual, even non-sensical - and it is because that’s what trauma feels like.

I’ve been diagnosed with complex post-traumatic stress disorder, and on that day of this somatic re-integration, it was the 9-year anniversary of the unexpected death of my friend Marc in a tragic motorbike accident. It was also 10 days from the anniversary of my grandfather’s death and about a year after my near-death road experience.

C-PTSD is a tough nut to crack. Not only do you have multiple items to work through, but often your nervous system is in such disarray that every next highly emotive moment gets thrown in with the rest as an additional trigger source. “Got 7 big ticket items to work through? No worries, we will just put this next ticket behind it, for when you are ready.” Like some fast food restaurant after a football game, only a whole lot more consequential.

Just like a movie can take us on a journey in your living room, somatic re-integration, can sequence an otherwise unknown or incompressible time period. Russell Crowe is not actually Maximus Decimus Meridius. Russell Crowe is not actually the commander of the armies of the north. Russell Crowe is not actually a General of the Felix Legions or a loyal servant to the ‘true emperor’ Marcus Aurelius.

But Russell Crowe, Ridley Scott and David Franzoni were able to pull together characters, places and symbols that spoke to that time. That enabled us as the audience to experience a period of the past and make sense of it, all under the one-word umbrella of Gladiator.

The bike I was on, the bike my mate was on, was not only symbolic of grief and fear but also shame. It was the device I had considered using to achieve the same result I grieved and feared.

After the death of my friend, and before the wrong decision to over-take a lorry, in a particularly troublesome period of my life, I found myself doing laps on a motorbike at 2 am in the morning.

I was devoid of hope, frustrated, and wondering to myself whether I had the courage to cross the middle line and take away the pain. Yes, courage. You read right. How confused we can become under sustained pressure that we are capable of murmuring these words to ourselves. No doubt we can all agree that ‘the courage’ comes from living, and I’m glad somewhere inside of me ensured I would come to that conclusion.

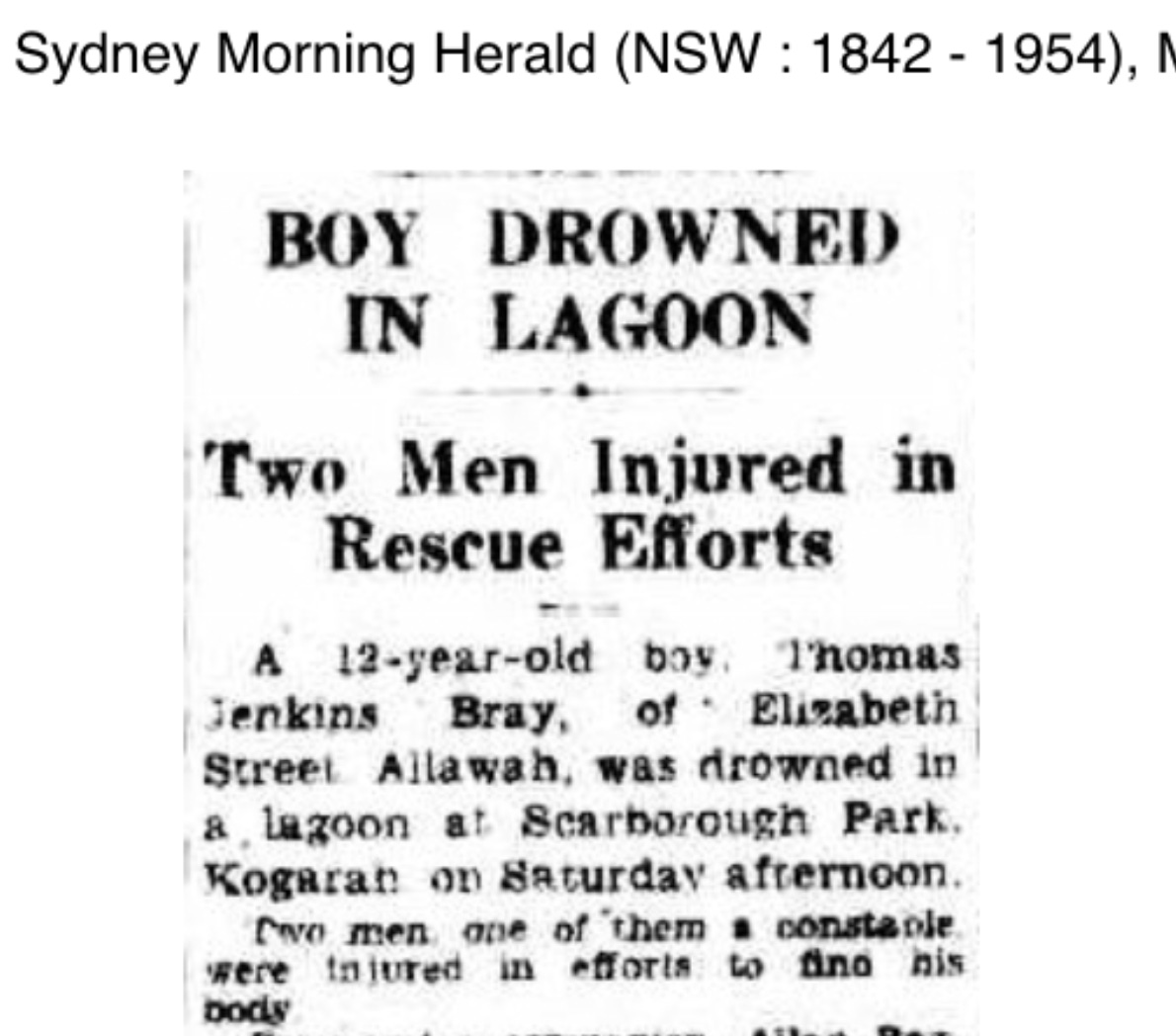

The loss of a friend in my youth was also multi-dimensional. It was something I had in common with my grandfather. Battling cancer in his final days, he disclosed that his life was never the same after he lost his friend in a lagoon at the neighbourhood park. 74 years prior to that disclosure, the event still haunted him. He said there wasn’t a day he didn’t think about it.

He was not only present at the drowning but he was also faced with an unenviable decision. His friend was entangled in the long weeds at the bottom of the lake, unconscious, and my grandfather had to make the decision to keep struggling to try to pull him free and risk losing his own life, or finally let go. He was only 12 years old. His decision to release his grip and rise back to the surface means I am sitting here today.

It's worthwhile adding I probably wouldn’t have comfortably shared this cross-generational story today if it wasn’t for the validation provided by the work of Mark Wolyn, the author of ‘It Didn’t Start With You.’

Reading the incredible story of Jesse, a therapy client of Mark’s, describing his insomnia at the age of 19, accompanied by feelings of extreme cold, was, what I like to say, ‘mind opening.’

Sometimes, data is useful as a wedge into our well-worn paths. It doesn’t necessarily need to be transformational. Or hopping from one camp to another. It is very simply loosening the grip we have on ideas and habits (many subconscious) that may have taken us to places we do not wish to go.

Back to Jesse. Jesse had a relative who, some 30 years prior, froze to death at the same age, 19 years old. He had been checking power lines in the frigid Northwest Territories of Canada and succumbed to the elements. Mark was able to use this as a thread that bound the past to the present, the logical to the confusing and through his protocol, bring about healing for Jesse.

Through what I described to you, I was able to embody the feeling of sitting frozen on the edge of my bed after being woken up by a phone call informing me of the death of my friend.

I was able to externalise the confusion and bring the emotion into the physical space by having some distance between me and what disturbed me, and by reliving what my grandfather was never able to process.

I was able to let go of the pain that was unnecessarily being held on to for my friend, which in doing so, was a disservice to the memory I dearly wanted to protect.

This was achieved through an intergenerational integration that provided me with the opportunity to describe what was indescribable with puzzle pieces that finally fit.

This is nothing new. We once had this type of communication firmly embedded in our rites and rituals. An Indonesian friend of mine, who lives in a traditional village, said to me once, “When I worry too much Jason, I walk down to the river, even if it’s 2 or 3 am in the morning, and I speak to my grandfather.”

I said, “Wow, your grandfather is very nice to allow you to wake him up at that time of night!”

He turned to me and replied, “No, no, my grandfather has been dead for many years. He doesn’t need to sleep. So I can talk to him whenever I want.” A big smile spread across his face.

What an attitude. Again, ‘mind opening.’ Not necessarily stepping into someone else’s cultural communications, but just to ask ourselves, what would it feel like to speak to ‘the universe’, ‘that friend’ or ‘that family member’ for a little bit of strength or advice when life feels all too much?

I left something rather important out of this post-game recap that is equally important, encouraged by another mentor, Dr Peter Levine.

Completing the incomplete

There were timelines, there were events, and there was bringing the emotional into the physical space - but there was also a completely unprompted and, in my truth, unmistakable completion of an action that my body wanted to do. The pulling of that brake.

I was introduced to Dr Levine by my current therapist (who we will speak about a bit later), and I felt immediately drawn in.

One of his clients forms an incredible case study. Ray, a veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan had been diagnosed with severe PTSD, chronic pain and even Tourettes. To Dr Levine, this last part made no sense, “You don’t get Tourette’s Syndrome overnight.” But Ray certainly had a jerking motion in his neck and head.

What Peter was able to uncover, was that Ray’s body was replaying a protective response from a moment he was victim to, over and over again. There had been a fire-fight, friends of his were killed, and then a blast sent Ray airborne. His head was still trying to find orientation and cover, from that explosive he wished had never gone off.

By unlocking that motion, by unfreezing the body, Ray was able to start processing the emotions behind it. That is to say, the body came first, which allowed access to emotions and only after that, a semantic storyline. Ray’s symptoms were almost entirely gone by the second session, and by the fifth, he was enthusiastically working through bigger questions, such as the shame and rage he was holding on to.

Dr Levine knew this intimately, not just because of his casework but because of his own experience of being in a car accident and the life-preserving actions he could feel his body wanting to do.

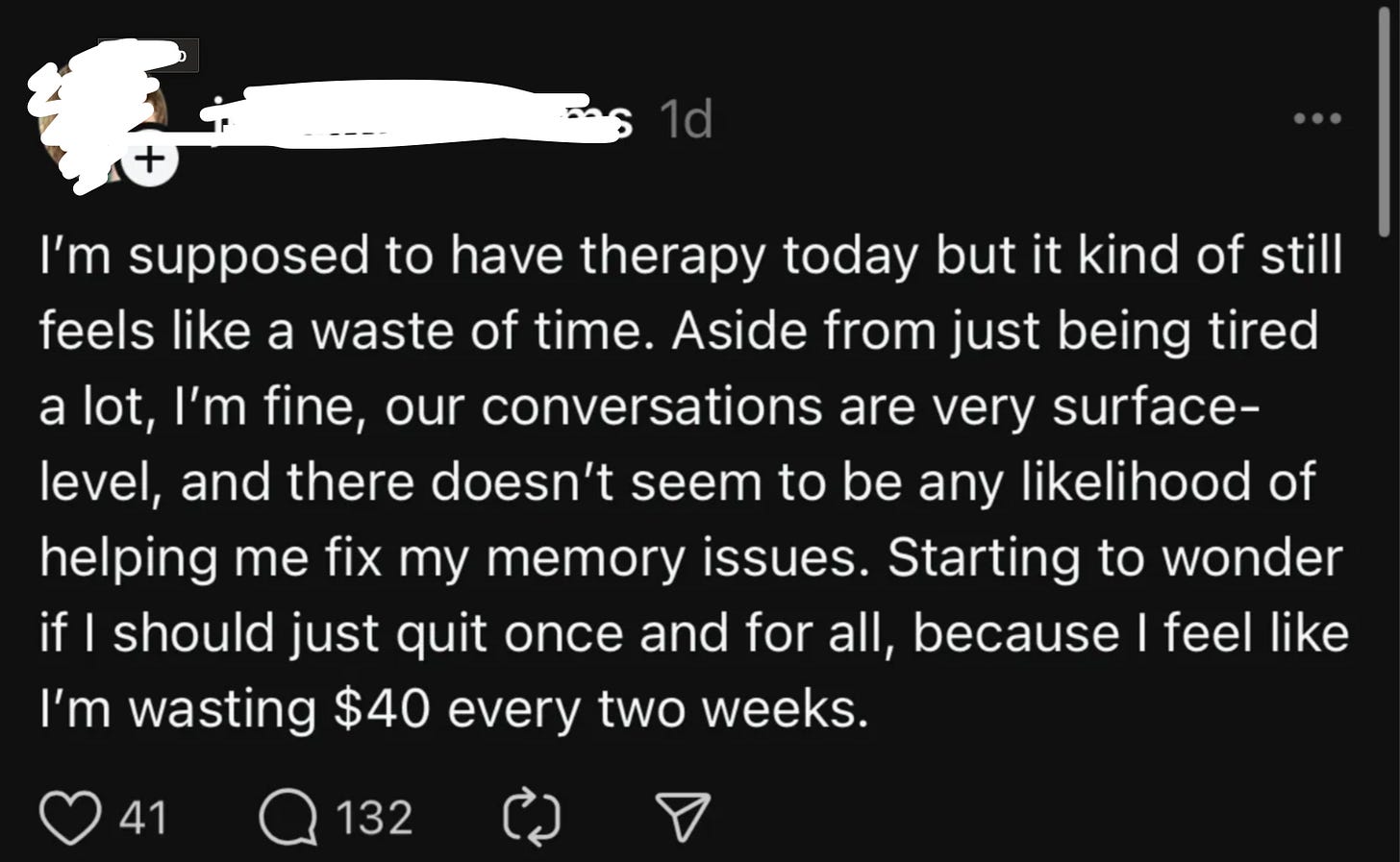

A post came across my screen only yesterday from someone newly undertaking therapy that stands in stark contrast to Ray, Jesse or my own story.

The user sharing:

“Our conversations are very surface-level, and there doesn’t seem to be any likelihood of helping me fix my memory issues.”

In scrolling through her answers to many concerned social media users, and putting aside the stand-out abnormally low fee being paid, it appeared this user has suffered a lifetime of abuse. Unfortunately for her, it seems her healing journey in response to that, is currently nothing more than sharing small talk with a stranger on the internet, with predictable results.

Body-led healing

Strangely enough, the near miss on the motorbike was not part of my c-ptsd of events to overcome. By the time I encountered that, I had been upskilling and engaging in self-directed re-integrations for some time.

What it enabled was a lot of ‘script’ accompanied by ‘feelings’ which tend to be the disconnect that is characteristic of trauma. When we create a distance to that disconnect but still hold the intent of closing the gap, we can put down the suppression, distraction and re-narration that are tools of self-protection for what is judged as too much to bear. A cocktail of self-soothing I had been implementing as my modus operandi for three decades.

After the near miss, I pulled over to the side of the road and turned the engine off. I scanned my body and spoke softly to myself, identifying what I found.

“Fast heartbeat”

“A very tight chest”

“Rapid shallow breathing.”

“Tingling fingers and feet”

What’s interesting, is those same symptoms arose at the beginning of the integration I shared earlier. My breathwork routine of deep, slow, vibration breathing was interrupted. From my therapy journal:

“I couldn't complete the vibrational breathing I was doing, my breaths were getting shorter, and my heart rate was rising”

I didn’t fight it. I knew what was happening. It was doing exactly what it was meant to do.

We know, thanks to the detailed work carried out by Dr Bessel van der Kolk, author of ‘The Body Keeps the Score’:

“The past can be relived with an immediate sensory and emotional intensity that makes victims feel as if the event were occurring all over again.”

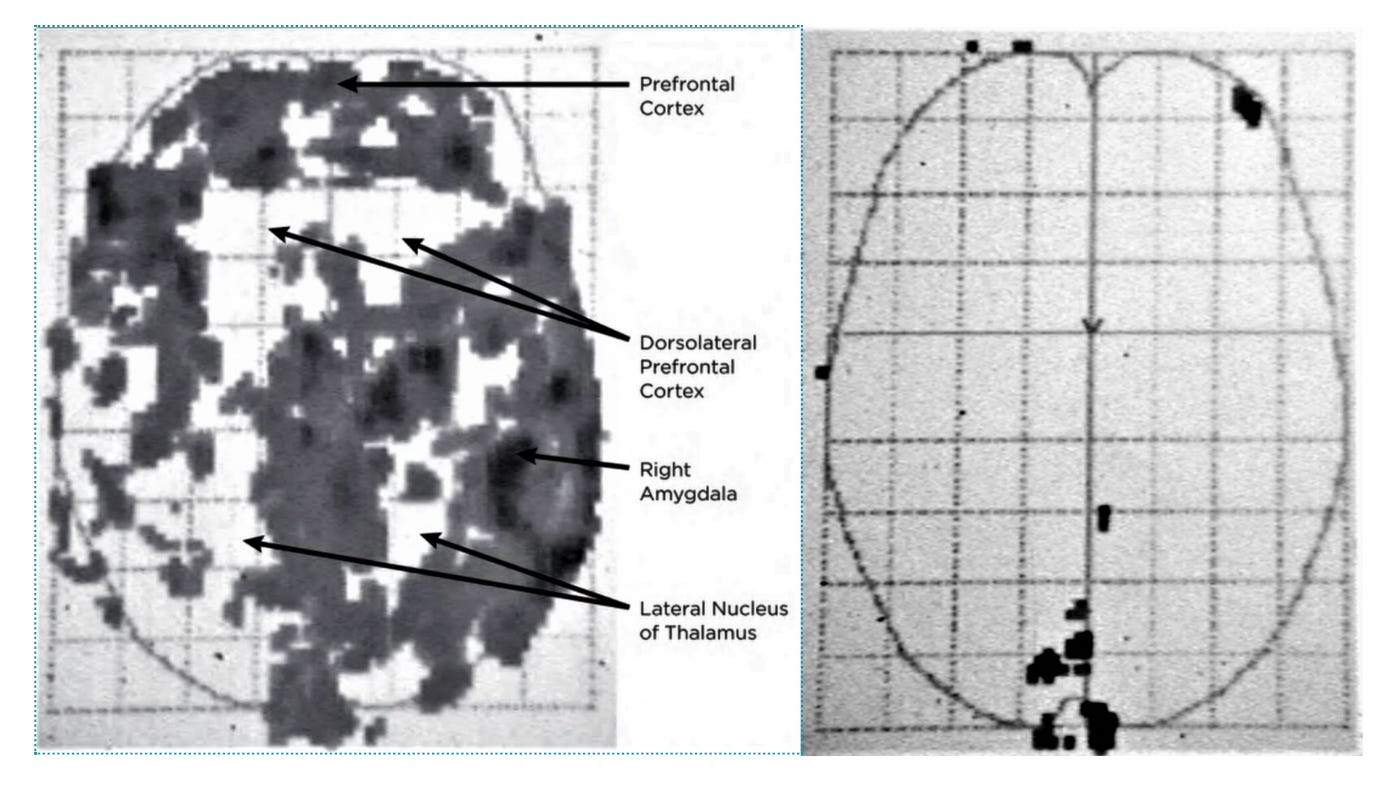

Brain studies of Dr van der Kolk, reveal the complexity of what that looks like.

A couple who were involved in the same car accident whilst reliving the trauma had polar opposite responses. Stan (the left image below) experienced hyper-arousal, whilst his wife Ute (the right image below), experienced hypo-arousal, better known as the shutdown response.

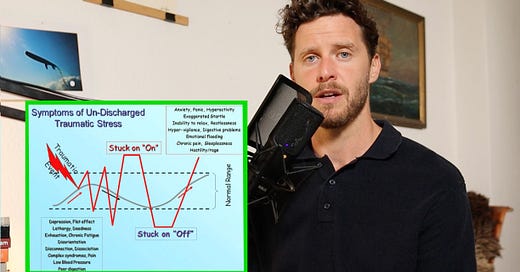

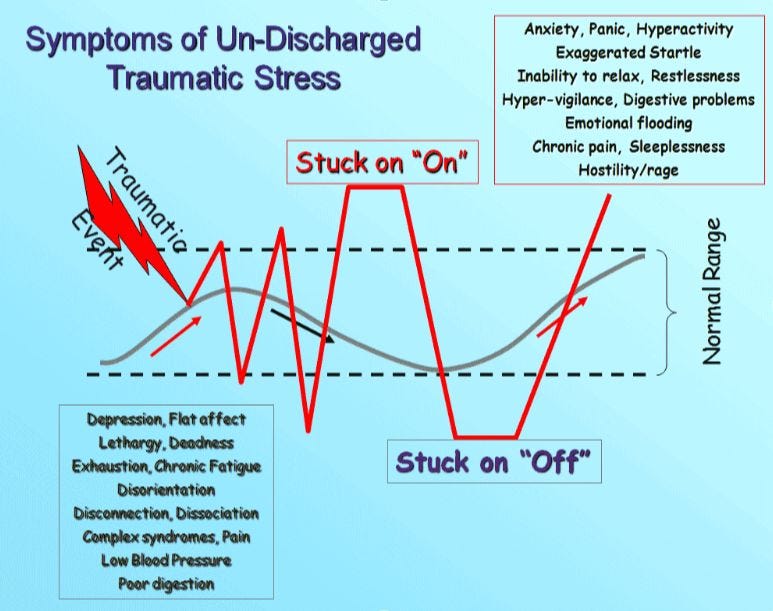

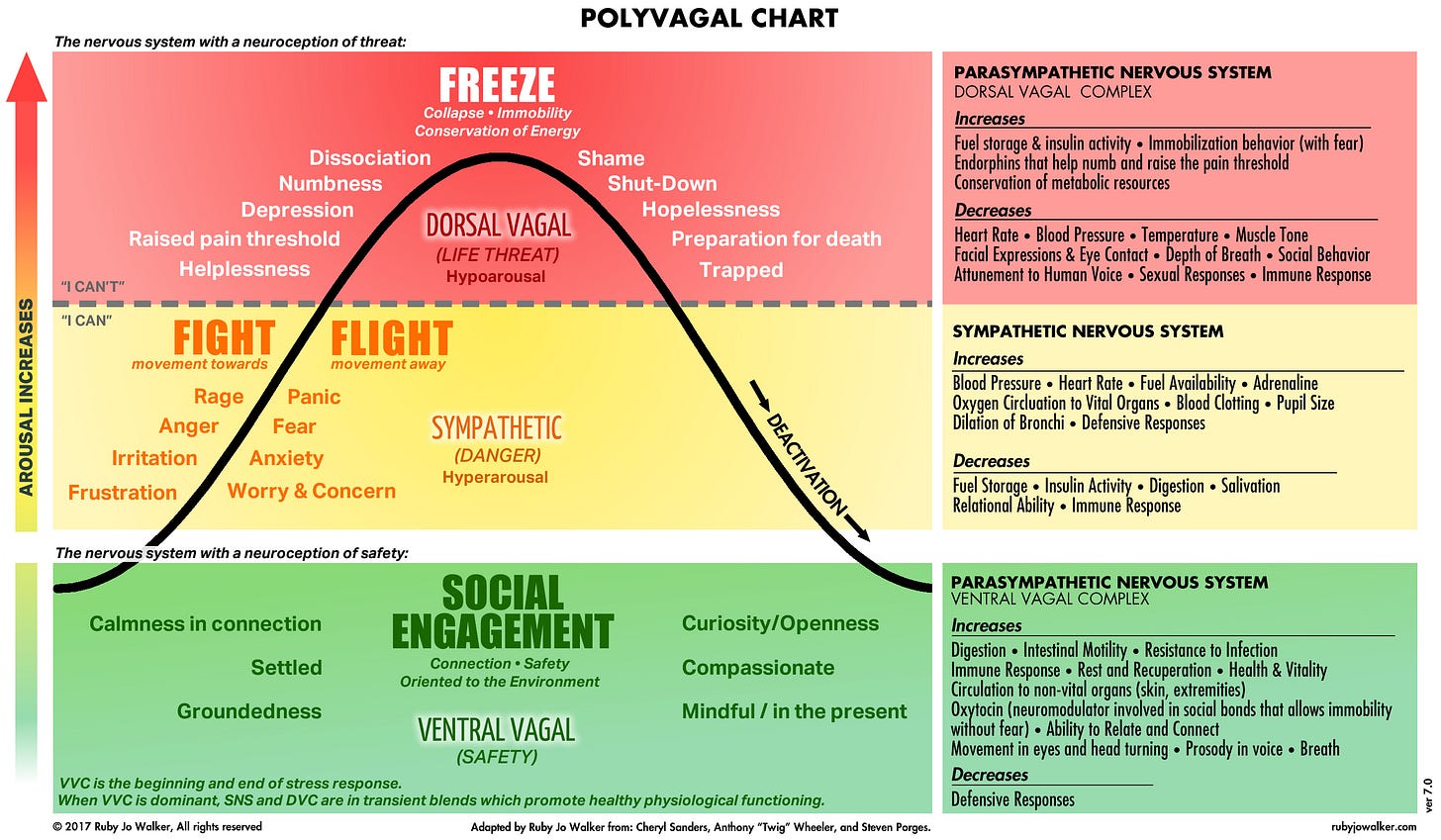

Before we start self-identifying with where on the spectrum of hyper or hypo we sit, at least in my experience, it can differ depending on circumstances. This chart explains that contradiction:

Instead of ‘one style’ we can oscillate between complete dissocation, or unrelenting rage. This adds to the confusion of trauma as ever more uncertainty is added to the daily occupation of our bodily vessels.

Going a layer deeper, Dr van der Kolk has revealed the difficulty for people who have experienced trauma to verbalise what they experienced or are re-living is due to the parts of the brain responsible for that becoming overwhelmed. Namely the hippocampus and Broca’s area.

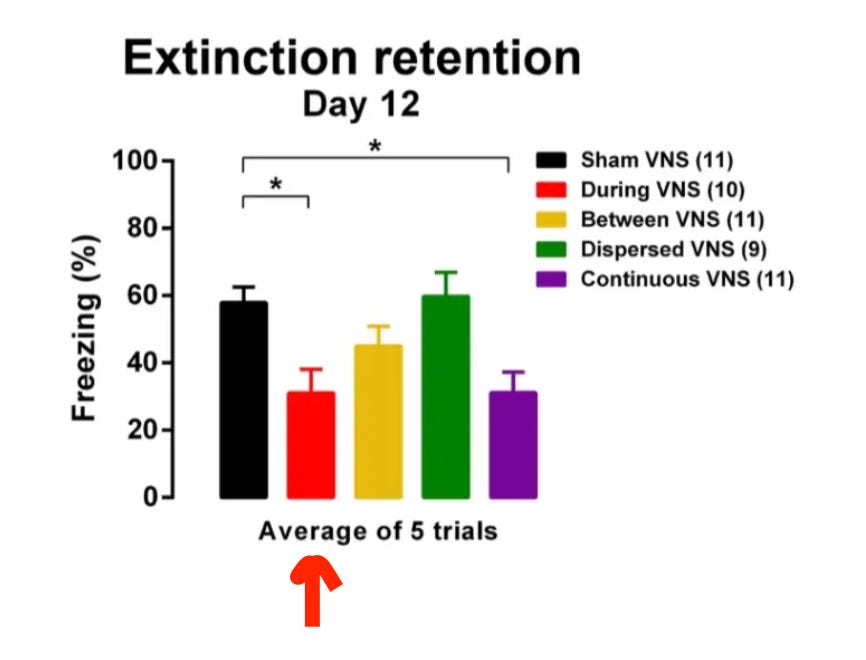

But re-experience we must. As experiments in rats have shown, the ability to extinguish fear when a modality is implemented, in this case, vagal stimulation (VNS), is most effective when carried out whilst the conditioned fear is being represented.

Trauma doesn’t just look out for like-for-like triggers, it expands the error rate dramatically, so fearful of a repeat, that an accidental threat detection is preferred over a missed threat. This means even the most distant reminder of what we felt in our past can evoke the most extreme of emotions. The likelihood of that trigger event happening increases the importance of having a toolkit of containment to see that out.

The critical balance we must strike is to work through our trauma, not around. First by the body, whilst keeping the wiring still working. Next feeling what needs to be felt. Lastly, placing together the fragments of the story that are yet to be comprehensible.

That may seem like a lot, and if it does feel too much, that’s ok. What’s important to realise is that it is possible.

This is the ‘after’ data. For the first time in 21 days, my temperature went down whilst asleep that night. I find this metric one of the most psychologically sensitive data points of my sleep tracking, superior to Heart Rate Variability or Resting Heart Rate. If I am emotionally triggered, I run hot.

What’s confronting is that we are designed, when the engines are running smoothly, to drop in temperature every night. And the flow-on effect of not doing so seems to have become more evident.

One study showed that people with a body temperature above 36.83 degrees Celsius (98.3 degrees Fahrenheit) were 2.6 times more likely to be depressed. This prompts me to ask myself in less buoyant times, am I triggered, or am I inflamed?

For the days leading up to the anniversary of Marc’s death, I felt unsettled, with brain fog and difficulty sleeping. After that session I felt light, I felt like I had resolution. And for the first time, I could talk about any of those topics that represented scenes in the story arc, without breaking down.

I want to be clear, this type of ‘intergenerational, somatic-based, re-integration of traumatic memories’ (or whatever word salad you chose to describe it), was not something that came naturally or really even by choice.

That being the case, I think it would be worthwhile sharing the lead-up to this day so that you can identify the location along the way where you currently stand and see if there might be a helping hand or pitfall to avoid that will assist your journey back to wellness.

x x x

The last flicker of hope

We have to rewind the tape to a time I was laying on a different floor. Not welcoming emotions, but trapped by them. Not feeling empowered, but feeling full of fear. The ground beneath me was my living room, and I had my head pressed against the door with one eye open, peeking to see if a neighbour was in the hallway before I ran out the garbage. The only reason I considered leaving was because it had piled up to a level I could no longer safely ignore.

Broken. Torn down. Burnt out.

I had just quit my job. Not the Hollywood style, a big speech and paper thrown in the air, but by email and very simply never going in again. It was cowardly, but the only thing that made sense, that felt safe. I was turning in because everything out there was too much. I didn’t even know what exactly out there was causing me to feel like this, and that’s exactly why everything had to go.

Naturally, this is not the activity of a functional 20-something-year-old, and so thankfully, my mother arranged an appointment with the family doctor to see how they may be able to help. After answering some questions, he referred me for six sessions under a youth mental health program.

About a fortnight later, I was walking up the stairs to the psychologist's office. I stopped sheepishly at the receptionist’s desk, averting eye contact and mumbling, “Ah, I have an appointment, Jason Field.”

“Take a seat, Mr Field.” The receptionist replied.

I meandered over towards the 3-year-old Marie Claire magazines splayed out across the coffee table and sat down, hands held together in my lap, shoulders slumped, like an 8-year-old kid having been sent to detention.

“The doctor is ready for you”, the receptionist called out after a short wait, “You can go in now, first door on the right.”

I walked in, my mother with me, as if, continuing the detention metaphor, we’d come to see the principal, I was about to be berated for unruly behaviour. That would have been preferable. To be a kid without rent or a boss.

The room was ‘modern’ in the way that all life had been stripped of it. Colour was only permitted to pop from an Ikea print on the wall, no doubt a limited edition of 1.5 million seen in homes and offices across 63 countries. A half-empty box of tissues sat atop a small table positioned between us and the professional, a sign of the poor soul’s distress that had come before my allotted time slot.

Looking out over the top of her glasses, with a clipboard in one hand and a pen in the other, the doctor asked matter of factly, “What brings you here today?”

Appearing to listen to my confused attempt at a conversational train of thought, she would drop ‘mmmhmm’ or ‘okay’ or ‘uhuh’ at irregular intervals, as I laid out the facts of my recent unemployment and persistent anxiety. Finally, she book-ended my babbling with, “Well, where would you like to start?”

Strangely enough, I didn’t start with panic attacks, insomnia or hopelessness - a far more frightening concern was the threat to my identity. I no longer knew who I was and what this cage I called the human body could be responsible for - despite my alternate desires.

I felt like I was living multiple lives.

One day I was looking after the financial needs of the movers, shakers and tastemakers of Sydney. A private banker for ultra-high-net-worth family offices. I would host meetings, present proposals and network better than most. I’d dedicated my entire life to gaining a foothold in such a position.

The first of my working-class Field family to go to university. The grandson of a butcher, the great-great-grandson of a penniless straw hat maker who had travelled 3 months on a sailing boat for a fresh start at the bottom of the world after the family was devasted by the agricultural depression of 1895.

There was no financial distress in Australia, I had secure employment. And yet my mind, body and soul, at the next unpredictable moment, had me peeking out underneath my door like a fearful rodent. I had a beard, a car, insurance - how could this be what I was to become?

Explain that to me Doc.

In what I figured was an attempt to begin to understand how to answer that question, she turned to my mother and said, “What was he like as a child?”

Mum told a few stories.

That I was quite sick. I almost died at 18 months and again at 10 years from asthma attacks. I often had to take a lot of medications, I would be hooked up to a venilator machine before going to sleep at night. The soft humming of that machine I seem to be replicating under the lull of Pavlovian conditioning with a current pedestal fan next to my bed.

That I spent a lot of time alone. Whether it was kicking a ball, constructing Lego or diligently doing my homework as soon as I got home from school - but I would make one exception, for my dogs. First Tessa, and then when she passed away Roy. “He loved those dogs, we all did,” Mum said.

Before long the first session was up. As I got up to leave the doctor reached into a plastic sleeve and pulled out a photocopied piece of paper, handing it over to me.

At first, I was excited, thinking it might be a treasure map to understand what was misunderstood. This great separation of self. But I was wrong and that sinking feeling in my stomach returned.

On the piece of paper was a cartoon with the heading, ‘Catastrophizing, what is it?"‘

Ouch. I felt about 2 inches tall. Already comparing myself to a rodent or a pre-pubescent child, my shoulders fell further and my eyes trained on the floor, bowing in worthless servitude to the all-mighty anxiety. Here I was with another label ending, ‘catastrophizing.’ The same result I always got from the white coats. Asthma, allergies, hyper-hidrosis, sever’s disease, IBS, irregular heartbeat. I would show up, they would diagnose. Nothing much changed.

The government program offered to co-pay for these sessions, six as I mentioned earlier, but only if you went to all of them, so I did.

In the follow-up sessions, we discussed questions such as:

Why do you think people in your office can still be at work now, but you can’t?

Maybe medication would be a good idea to help you get back to work.

Let’s have a chat about what ‘projecting’ looks like…

That flicker I felt when the loose leaf of paper emerged from the plastic sleeve was the closest I felt to hope in quite some time. But that flame, like an oasis in the desert, or trying to light a candle in the wind, had nothing for me now. And so I just went through the motions.

I would like to confirm here that those questions, in isolation, are not terrible.

Supported self-inquiry via objective observation of another? Sure, sign me up. Building a table of mentors has been a non-negotiable part of my journey back to functionality.

The difference, though, is the timing. That, for me, is where we begin to draw the line between the contemporary mass market approach to mental illness and the path that I ended up taking (following others before me) and what we will continue to expand upon.

When we are in breakdown; comparison, labelling and intellectualising the situation is, in my opinion, highly counter-productive. But I’ll let someone with a framed certificate on their wall explain that more clearly. From Dr Stephen Porges:

“Therapies often convey to the client that their body is not behaving adequately. The clients are told they need to be different. They need to change. That kind of therapy in itself is too judging of these individuals. And once we are evaluated, we are in defensive states. We are not in safe states.”

If our body is in such a state that a grown man is struggling to emerge from his apartment, and the most logical resolution from his current decision-making matrix is a one-eye-ball observation of the apartment hallway and email resignations, then maybe, just maybe, we aren’t operating in a field of logic and reasoned debate.

Perhaps there are a few missed steps along the way. A return to safety. A re-engagement with the nervous system through validation of sensory experience.

There has to be something else

With the failure to download better mental models in an Ikea showroom, I am thankful my nervous system ‘projected’ significance onto calm-oriented activities. Having removed the big ticket of an 80-hour work week, at least temporarily, I was feeling some breathing room, and I began to broaden my search for answers in order to get back to the trajectory I’d worked so hard for.

It wasn’t a passionate pursuit of calm, it was a cocktail of:

“Give me something so I can get something else that I want”

“My backs against the wall, so I may as well try this”

“Give me one more chance”

In almost every one of the six sessions I attended, I was prompted with the ‘seed’ to ‘think about’ the ‘idea’ that medication was the best path forward given my current state. And I really didn’t want to go down that path, at least not yet.

I tended to be a person who showed side effects that no one else did. The fine print item 7986 on the medication leaflet that ends up in the bin unread, is often written for me. Even outside of the stocked medications for my ailments, a strong paracetamol could be enough to cause me to lose coordination and walk into my bedroom wall.

There had to be something else available.

Scanning the internet at night, before ‘healing is the new hustle’ or ‘when the body says no’ or ‘trauma’ as a hashtag, it was incredibly difficult to find accessible information and resources. A role model who stood out was a local TV presenter coming clean in the tabloid section of the newspaper about recent successes with a meditation teacher for overcoming anxiety. Perhaps headline-grabbing gossip, perhaps not. I thought it better to go into a room of the ‘elephant pattern pant’ wearing person, that has at least been tested by someone who wears a suit for their day job. A distant referral of sorts.

Booking online, I was nervous. I had little hope it would work. I only pictured Tibetan monks in robes sitting on a mountain chanting, not people like me, but I was very lost. Everything ‘normal’ seemed to have failed me, and at least the commitment to going was buying me a little bit of time to live in the belief I was helping myself back towards recovery.

Saturday morning came around and I was barely able to walk into the inner city household of this apparent guru. Not from social anxiety, but from a chronic hangover. I had gone out the night before and soothed myself the same way I had since I was 14, by getting blind drunk. That may sound confusing after sharing stories of prohibitive social anxiety, but it is surprising what a few, or a few too many, warm-up drinks at home can do in the form of liquid courage. The last thing I felt like doing was smelling incense and being surrounded by too-good-to-be-true happy people, but I entered nevertheless.

Surprisingly, sitting in a circle around Tim, the meditation instructor, were people like me. Really like me. Stressed out, eyeballs red, living only on the remnants of cortisol and adrenalin. Their battery pack was well past their peak, and with no downtime to re-fill, they, too, it seemed, were making a last-ditch effort at ‘could this work, when nothing else has.’

Comfortingly also, Tim shared a story of growing up and having similar difficulties with modern life as I did. Meditation was simply a tool that helped him. It helped him so much that he wanted to help others. That sounded logical, even to my irrational monologue.

Before I knew it, we had our eyes closed and he was guiding us in our first meditation. It was one of the most powerful experiences of my life. I felt like I dropped into a deep pool of consciousness that I had never before even touched. I think the hangover may have even helped, by making me even more emotionally vulnerable, that exposure leaving me ripe for a mentor who knew what to do in such a moment.

We each had a small one-on-one chat, where I felt incredible warmth and was close to breaking down in tears, my hair literally standing on end. The tears I shed in the psychologist's room were shame tears, sad tears, and confusion tears. The hint of tears that welled in my eyes sitting across from Tim was reverence and relief. I was in the presence of someone who had done the work and who had the capacity for another. Capacity, not need, not extraction, not re-narration or labelling. But that he could withstand holding some of the crushing load written across my face and sitting atop my shoulders, if for just a weekend. It was a remarkable glimpse at the other side.

That all sounds very powerful, almost a salvation of sorts from the breakdown I was experiencing. If it was though, a salvation, there would be no more story to tell. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, depending on how we look at it, I had a lot more to learn.

What I ended up doing with that tool learnt after 15 hours of practice that weekend, and then each Monday evening at Tim’s online workshop, was to use it as a reserve battery pack. Almost like those portable batteries, we recharge our phones with when we are away from an outlet. I certainly felt that I could touch a level of down-regulation, and that I could allow an energetic recharge, but the question begs, what do you do with that energy?

What I did, was to continue to interact with the world in exactly the same way as I did before, with just a little extra juice in the back pocket.

I got relatively functional again, but looking back now, I realise all I was doing was dancing on the same stage, with the same script, with slightly different characters and costumes. I don’t say those words lightly because what I wasn’t to know after leaving Tim’s inner city townhouse is that I would break down again 3 years later and again 3 years after that.

I had no idea about the equal time intervals until recently when I was pulling my notes together, perhaps we have a battery inside us that flashes red at predictable times to allow such seasons of repair? Especially when we refuse to admit that limits exist or that we may be playing the game in a non-profitable way. Like a coach calling us off the field, we get benched, suck on some orange slices, gulp down some Gatorade and then scurry back out for more hits on the field of life.

What happened between breakdown 1 and 3 we will fill in another time, what’s important right now is to come back to the original question, “I have anxiety, where do I start?…”

What happened between breakdown and self-directed re-integration is a better story to tell in an effort to answer that question.

Alpacas? I’m in

It all started with a phone call in my kitchen.

When we put our hand up for help and it’s instead high-fived, what do we do?

We tried talking through, we tried settling down, but still, here we are broken once again and looking back on a track record that was starting to look less like a misstep and more like fate.

I began asking myself a few questions about what made me happy when I was younger. When all else failed, like what I was feeling right now, what did I go to?

In my childhood home, along the back fence of the yard was an elevated retainer wall that had big conifer trees planted in it. Designed as a privacy screen for the neighbours who built their house against the other side of the fence, to me it was a privacy screen against the entire world.

Running along the grass, leaping up on the brick ledge and crawling beneath the branches was my very own The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe portal. An entryway to an alternate world, where the other world, that made me sick, that kept me up at night, that upset my stomach with nerves, wasn’t real anymore. My hands and feet in the dirt, often holding my dog tightly, nothing else mattered.

As I grew older that same attachment was felt with the ocean. At five years old, with surf life-saving training called ‘Nippers’ that prepares young kids for the ocean. At 15 years old, riding my bike after school with a surfboard rack on the back. Later, driving my car after work, ripping off my jacket and tie and diving into the big blue yonder.

Each time I left the shore, the only thing that mattered was the next wave coming towards me from an infinite horizon. When I looked forward at just the right angle, I knew the next stop was nothing until Antarctica. That’s penguins, not people. That’s turtles and whales and leaping dolphins. The chaotic crowd behind me were nothing more than ambient noise of decreasing concern.

Nature was a constant in the face of unexpected bad news, bad events, and even bad people. I would go to the ocean, and try to wash it away. When Marc died, we celebrated his life with an ocean ceremony. It was a flat day, barely a movement on the surface. As we all joined in a circle to say a few words, a solitary wave came through, raising all our boards like corks bobbing in the ocean, before dropping us and continuing to its sandy destiny. I don’t need to describe that further, it is what it is.

Maybe waves and the ocean are scary for you. I’m not great in the snow. I have only skied once, and I mistook the orange poles for a slalom course (after watching the Winter Olympics). I went flying off a ledge and landed face first in the ground to the dismay of onlookers. “Didn’t you see the warning poles?” A kind man asked me as he helped me to my feet. I was too in shock to reply.

Whether it’s the ocean, mountains, forests, painting, music or the Chronicles of Narnia, I’m sure there was something in your youth that fascinated you and perhaps even made you feel calm.

With that filter in my mind, I began searching online for people that I could talk to who would talk back in this language of my safe place. I came across a directory and read the biographies of listed therapists. One stood out, Josh.

He lived 5 hours north of Sydney on a farm with alpacas. He surfs, plays the didgeridoo and holistically heals through counselling and yoga therapy. I thought that was worth a shot. Even if he is no good at therapy, at least we could catch up about the latest surfing world championship event.

The next week I took my laptop to the kitchen table, brought a box of tissues with me (that’s the routine right?) and opened up Zoom. Within a few moments up popped Josh. He said, “Hey Mate.”

Boom. My language. I could have hugged him right there if it wasn’t for the 16,000 km that separated us, given I was living in Germany at the time.

“How can I help you today?” he followed up.

I ran through the scenario, like I did 6 years prior, with eerily similar descriptions.

“I can’t go to work.”

“I’m looking under the door before leaving my apartment.”

“'I’m having these trembling panic attacks that have been getting increasingly severe.”

“Sounds like you’ve had a tough time, sounds like you are still going through a tough time.” He mirrored.

“Yes, yes.” I replied.

“I can understand. I’ve been through something similar. The shakes, the unknown fear, the isolation. It is your body trying to talk to you. It will speak quietly at first, until it needs to scream for you to listen, to pay attention.” He said.

Hmm. Weird. I talk. My body moves, it doesn’t talk. What was this guy going on about? It seems like his long hair and flower button-up shirt have overwhelmed his reasoned mindset as well.

I followed his empathetic vulnerability with the only topic that mattered to me, “So you have anxiety too?”

He replied in quick succession, “Nobody has anxiety, everybody can experience anxiety under the right, or rather wrong conditions. It is a response from the nervous system to what it is facing.”

These words are like second nature to me now, but at the time, and under the conditioning of my life experience, that felt warm and fuzzy in my stomach and heart, but in my head, I struggled to digest it.

When we tease a little release of our feelings or have a flat-out meltdown, often what comes back to us is an invalidation of our experience. Especially when we are young. That narration becomes internalised as our working definition, despite its distance from our truth. Being confronted with an acknowledgment of your reality decades later can feel just as foreign as the false, purely because it is not yet an acquired taste.

We chatted some more about the difficulties I was facing before our session came to an end. Josh said that if I’d like to continue the sessions (it was an introductory call), next we will be finding out where I picked up these bags I am carrying, and see how we can go about putting them down.

No labels?

No comparisons?

No intellectualisation?

Instead:

You are experiencing anxiety, you don’t have anxiety.

You are carrying bags, they are not you, and likely someone else put them there.

Those bags can be put down, and here is standing evidence from someone who has already done that.

Suffice to say I was highly motivated to book the next session. A big difference to co-pay compulsory attendance half a decade ago.

And so our journey began, he sent me an email with a yoga sequence to practice and we set up our next call.

I was excited, could this be the turn around?

Relapse

About a week later, whilst doing yoga, my hopes faded. That dreaded feeling came over me. First in my head, as it became light and my sense of mind’s eye distorted, and then my stomach, as it twisted and turned with the sheer fear of near death, and then the trembling.

Panic attacks do have a lot in common for those afflicted by them, but they also have unique signatures that are catered just for us. For me that was waves of muscle seizures that would often bring me to the floor (there’s that defeating place again). As it did that day.

For our next session, the screen popped up, and a now familiar “Hey mate” came into my headphones.

Before even a follow-up question, I blurted out, “It happened again, I had another panic attack.”

At that time, I was almost accusatory. As if, we had signed a contract that if I sit down and talk with him, the panic attacks would stop, but they didn’t, has he let me down?

He calmly replied, “What was it like?”

I thought, who cares about what it was like, it was bad, all panic attacks are bad, now make them stop!

The aggressive thought, as often happened, was filtered by my people-pleasing ways, and I endeavoured to answer his request.

Well, it happened doing your yoga routine. It was a lot of shaking, really scary, I thought I was going to die.

“That’s understandable, it can be really scary when you feel like you are losing control,” Josh said.

“Yes exactly, I don’t know why it does this to me, I feel like I’m in a war with myself.” I replied angrily.

“Have you ever had a dog as a pet?” he asked curiously.

I answered excitedly, “Yes, yes. I have had two boxer dogs. I loved them.”

“Do you remember seeing them do a big shake?”

What a strange question. But sure. I do remember my dogs shaking. Often they would shake after I gave them a bath while I was trying to dry them. Usually, it meant I got wetter, the drier they became.

He listened to me recount me running after my dog in the yard with a towel, and then asked, “…and what about times they shook and weren’t wet?”

Hmm, I guess there were times. When they woke up and definitely when they were excited to see me.

“Yes, it’s a reset. You’ll often see a dog ‘shake off’ after a near miss with a bike or a car as well. It’s therapy for the animal kingdom. If an antelope is chased by a cheetah and gets away, you’ll see it shake, shake, shake, the whole body convulsing, and then run off and return to grazing as if nothing ever happened. Same with most animals. A life or death situation brushed off as a slight inconvenience.”

He then hit me with one of the biggest questions I had encountered in my journey of trying to feel alright, rather than anxious and many times downright depressed.

“What if the body was trying to save you?”

And he didn’t stop there.

“If so, what do you think the body is trying to tell you?”

And the final knockout punch.

“How do you think you can support yourself in those times?”

I’ve never looked at a panic attack again in the same way.

Thankfully, it’s been a long time since I’ve had one, but now I see them as they were: a natural reset and energy release. In fact, I set up circumstances that welcome that same type of ‘animal kingdom therapy’ during the somatic re-integrations that I began this newsletter describing. Those shaking shoulders, those raising hips and outstretched fingers.

Remember the quote from Dr Porges about safety versus evaluation in therapy? He also has a useful graph to explain that in further detail:

After closing the gap from breakdown number 1 to self-directed somatic re-integration, where could you place the numerous examples we reviewed on that chart?

Perhaps Stan is in the middle third ‘fight or flight’, perhaps Ute is in the top third ‘freeze.’ Perhaps me leering under the door was definitely not in ‘social engagement.’

Again, the words of Dr Porges likely to surpass my attempts:

“I started in my talks to tell clinicians, ‘Try something different with clients.’ I said, ‘Tell your clients who were traumatized that they should celebrate their body’s responses, even if the profound physiological and behavioral states that they have experienced currently limit their ability to function in a social world. They should celebrate their body’s responses since these responses enable them to survive…Tell them to celebrate how their body responded instead of making them feel guilty that their body is failing them when they want to be social and let’s see what happens.’ ”

As always, to your healing 💙,

Jas.

I’d like to dedicate this post to my grandfather. A softly-spoken but incredibly courageous man who will always be the patriarch. I wish you could see me now Pa, I know you’d be proud.

And to my mate Marc, who still today tips me out of my comfort zone like he did at school. Whenever I am feeling low in confidence, I say to myself, “What would Marc do?” knowing full well he would push forward.

________________________________________________________________

Referenced literature:

Wolyn, Mark. It Didn’t Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle.

Psychalive interview with Dr Peter Levine: https://www.psychalive.org/interview-dr-peter-levine/

Threads user therapy experience: https://www.threads.net/@justsmalldreams/post/DBG2ia_O1bI

van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

Souza, Rimenez et al. Timing of vagus nerve stimulation during fear extinction determines efficacy in a rat model of PTSD.

Rausch, J et al. Depressed patients have higher body temperature: 5-HT transporter long promoter region effects

Porges, Stephen. The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe

Porges, Stephen. The Polyvagal Theory for Treating Trauma.

Zhang, Yi. Dopamine Receptor D2 and Associated microRNAs Are Involved in Stress Susceptibility and Resistance to Escitalopram Treatment

Ibrahim, Mariam. Father-Adolescent Engagement in Shared Activities: Effects on Cortisol Stress Response in Young Adulthood

Li, Di. 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase expressed by gut microbes degrades testosterone and is linked to depression in males

Ritz, Nathaniel. Social anxiety disorder-associated gut microbiota increases social fear

Trivedi, Gunjan. Humming (Simple Bhramari Pranayama) as a Stress Buster: A Holter-Based Study to Analyze Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Parameters During Bhramari, Physical Activity, Emotional Stress, and Sleep

SOOO good! I loved this article, the combination of science with everything you experienced & experience, all you tried & just this trust in yourself & your body you developed! I resonate with so much of it, without even having CPTSD or anxiety or such & that is a sign for me that it is generally applicable to all of us, cos I deeply feel it as the Daria = N=1 that I am. That is how it starts & this N=1 is sometimes the only thing that counts.

Thank you so much! I don’t have the words to properly express how impactful your words are but I’m so grateful to you for sharing them. 🙏🏼